The Science of Pointillism

Many of us were given white construction paper and some crayons at some point in the primary grades and shown how to make a simple color wheel. Sometime not long after that, we were taught about complementary colors. Exactly how we were supposed to employ that knowledge in our lives was lost to me for many years—maybe I had the flu the rest of that week.

I distinctly remember a time early in my undergrad years, sitting in a literature class at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, waiting for my fellow students to take their seats. I noticed a young lady enter wearing a red cashmere sweater over a white button-up shirt and a dark khaki skirt. I was reflexively reminded of the color wheel and how complementary colors were situated on the wheel across from each other. I also knew dark khaki wasn’t on the color wheel, but, to me at least, the sweater and skirt were perfectly complementary.

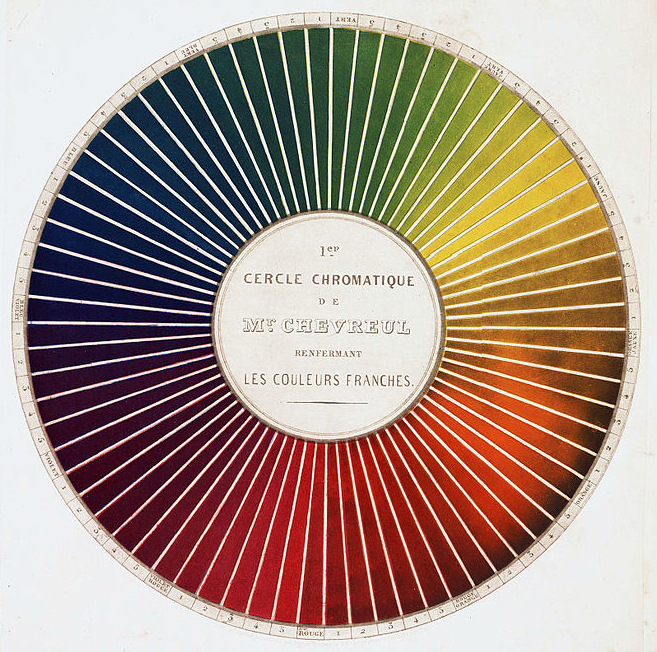

On a traditional color wheel, the complement to red is green (a primary color and a secondary color). This means that, at least in one theory, the complement of a primary color is the combination of the other two primary colors. A complement to yellow is purple (blue + red). If an entire piece of paper (or computer screen) were covered with alternating yellow and purple dots, the overall visual impression would be a gray field. This is taking color theory very simplistically, and varying theories exist on the subject, but you get the general idea.

The term “complementary colors” was coined by British scientist Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford in 1793. He thought this discovery would be helpful to ladies choosing ribbon color to match their frocks or to designers choosing wallpaper, curtains, and rugs. This was about the time scientists developed a way to measure wavelengths in the visual spectrum. Three decades later, a chemist at a dye works in Paris, responding to consumer complaints about inconsistent dye pigmentations, further developed Thomspon’s theory on complementary colors. Michel Eugène Chevreul developed a more detailed color wheel, and his findings were much sought by designers of gardens, fashion, interior décor, and printed material. I imagine a lot of beakers, mirrors, and Bunsen burners were involved.

Most important to me (a big fan of visual arts) was Chevreul’s influence on Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists. The Pointillism of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, among others, were based on Chevreul’s color wheel. These artists and others (such as Camille Pissarro) sought audience with Chevreul, and Vincent van Gogh made notes on his theories. So, the thousands of dots in Seurat’s large work A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (c. 1885) at the Art Institute Chicago (and, of course, featured in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off) were not necessarily chosen at random to create a soft and gauzy scene; Seurat’s choices were based on the scientific findings of a French chemist.

I just found that all interesting. The next time you run across things that just seem to look right together (like a red cashmere sweater and a dark khaki skirt, for example), try to think for a second about the crayon color wheel you made in grade school.